November 08, 2022

On Adult Life Changes

By Elisabeth Callahan, LCSW

FROM ELISABETH CALLAHAN

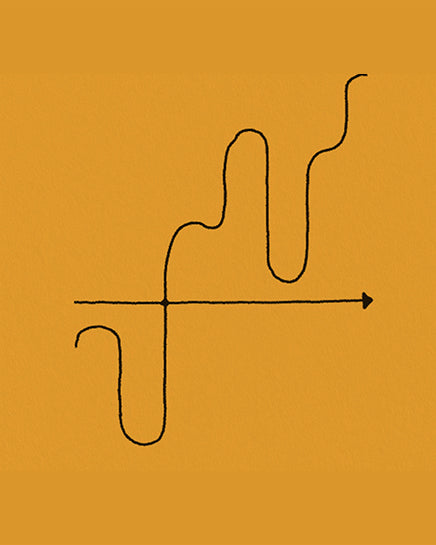

We all go through life transitions and events like graduating from school, starting a new job, getting married, having a child, or losing a loved one. Even if we're excited about what awaits us on the other end, transitions are often challenging and our brains can make them even harder.

In my work with folks moving through life transitions, I hear common cognitive distortions that negatively affect how someone navigates that phase of life. Cognitive distortions are a component of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), which posits that our thoughts direct our feelings which direct our behaviors. Therefore, our thoughts hold immense power to shape our experiences.

Cognitive distortions are irrational and persistent patterns of thinking, similar to filters through which we view ourselves and the world. Research shows that the frequency and use of cognitive distortions can help predict someone’s perception of life events as stressful.

There are several types of cognitive distortions and they are commonly used by every human being (although we each have our favorites or the ones we use the most). While I won't go through all of them, I will highlight a few that are easy to default to when going through a life transition.

SPOT COGNITIVE DISTORTIONS

All-or-Nothing / Black-and-White Thinking. We engage in this cognitive distortion when we paint our transition as either all good or all bad, with no room for the nuance or acknowledgement that the transition has both positive and negative aspects to it.

Example: You have been the caretaker for your elderly parent for the last few years, and recently, your parent has moved to a caretaking facility. You may automatically see all the positives associated with this change (i.e. you have more time, you're experiencing less pressure and stress, you can turn your focus toward your other responsibilities, etc). You may then be surprised or confused when negative feelings start to arise (i.e. sadness that you're no longer as involved in your loved one's care, loss of a sense of purpose or helpfulness, frustration by the financial costs associated with this change).

"Should" Statements. Often, if our new season is viewed as positive by external sources—such as family, friends, and the media—we might feel pressure to feel positively about it, and guilt or shame if we don't automatically feel that way.

Example: If you're having a baby, you might think you "should" feel elated about this event. This adds pressure to an already intense time and may cause you to feel disappointed in yourself, embarrassed about your hidden feelings, or overwhelmed and exhausted from withholding part of yourself and your experience.

Control Fallacies. We can either think we're in complete control of the transition or that we have no control over any part of the transition. Neither option is true, and both can cause us to feel stuck.

Example: You just moved to a new city. As a highly organized person, you have pre-planned your new living situation, new job, potential community and social opportunities, and possible neighborhood spots where you can grab what you need. So this transition should be easy, right? Not necessarily. While we have control over how we respond to a transition, it is incorrect and unhelpful to assume that we can plan our way to a positive transition.

EASE YOUR TRANSITION

What can you do to make your experience of a life transition easier?

Try cognitive reframing. Cognitive reframing is the process by which you can identify, challenge, and reframe your unhelpful, negative, and distorted thoughts about your situation.

The first step to cognitive reframing is reflecting on what thoughts come up the most for you about this life transition. For example, when I transitioned to my current job, one overwhelming thought I had was: I probably do not have what it takes for this position. What if they find out?

My next step was to challenge this thought by asking myself questions about the thought—similar to putting it “on trial.”

What is the evidence for and against this thought? Evidence for this thought includes the reality that I haven't yet had experience doing some of the things on my job description. Evidence against this thought includes my advanced degree and licensure, years of experience doing similar work, and getting chosen for the job out of other applicants.

What would I tell a friend who was having this thought? I would tell my friend that while it's normal to feel nervous about starting a new job, they have worked hard for their related work experience and to get this specific position. They can do it! They've done hard things before and they are up for the task of taking on this new job; learning, growing and showing that they are the right person for the position.

The final step is to offer a reframe to that thought. The goal of the reframe is to create a different, more neutral perspective that resonates with you (so you'll actually use it). It is not helpful to use an overwhelmingly positive or unrealistic thought to replace your negative thought. Using my example in the first step, the reframes I considered included: I have a lot to learn about this position, but I am up for the task. I am qualified for this position or I wouldn't have gotten it. The learning curve will be steep, but I've been in similar situations before and was able to learn all I needed.

Continuously working through this process (because it takes practice!) allows you to consider and experience your life transition from a different perspective. Identifying and utilizing a reframed thought allows you to feel more confident about your ability to manage the transition, which leads to you acting in ways that align with your intentions for how you want to show up during this transition.

Be kind and compassionate to yourself during this time, whatever that looks like for you. A paper on self-compassion, stress, and coping tells us that people who are compassionate toward themselves are less likely to catastrophize situations (a cognitive distortion) and experience anxiety after experiencing a stressful event. Try to recognize that you’ll likely have waves of different feelings, thoughts, and reactions to what’s happening. Pay attention to your body, doing your best to continue to take care of your basic needs such as rest, movement, and food. Transitions inherently bring different expectations and routines, and it typically takes several months to settle into a new situation.

Ask for support or help from those closest to you. We know that life transitions are stressful— even a person's perceived amount of social support influences their coping capabilities . Asking for help is not a sign of weakness, but rather a sign of knowing yourself and your needs, and working to get those needs met. Try asking for help using one of these questions:

As I go through this transition, I'm realizing I need help. I know I'm usually in charge of grocery shopping, but I can't do that at this time. Could you please do the grocery shopping for us for the next few weeks?

I'm feeling overwhelmed, and would like some alone time to take care of myself. Can we work together on figuring out childcare for the next couple Saturdays so I can have some time off?

Moving is hard and I'm feeling discouraged. Can you please remind me of the reasons I told you I want to move?

TIP OF THE WEEK

Make Cognitive Reframing a Practice Cognitive reframing is a coping strategy that can be utilized in many situations, not just life transitions. Give it a try to help you manage whatever comes your way, and make it an ongoing practice in your life:

Track your cognitive distortions. Think back on your day or week and ask yourself: What am I telling myself that's contributing to me feeling ______? Are these thoughts helpful or unhelpful in this situation?

Prepare in advance. Anticipate when your cognitive distortions might come up and proactively develop your reframes.

Repeat your reframes to yourself on a daily or weekly basis. The more you review them, the more they will resonate with you and become more integrated into your consciousness.

Elisabeth Callahan is a licensed clinical social worker in the San Francisco Bay Area. She incorporates parts of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), and Internal Family Systems (IFS) into her clinical work with women managing depression, anxiety, relational stress, self-esteem challenges, and seasons of transition. She enjoys spending time with family and friends, reading with a good cup of coffee, and baking sweet treats.

Subscribe or contribute to Waiting Room.

This article is not therapy or a replacement for therapy with a licensed professional. It is designed to provide information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is not engaged in rendering psychological, financial, legal, or other professional services. If expert assistance or counseling is needed, seek the services of a competent professional.